MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

|

PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

Friday, July 24, 2015

MOVIE REVIEW

The Stanford Prison Experiment

The State Of The State Of Authority, California, 1971

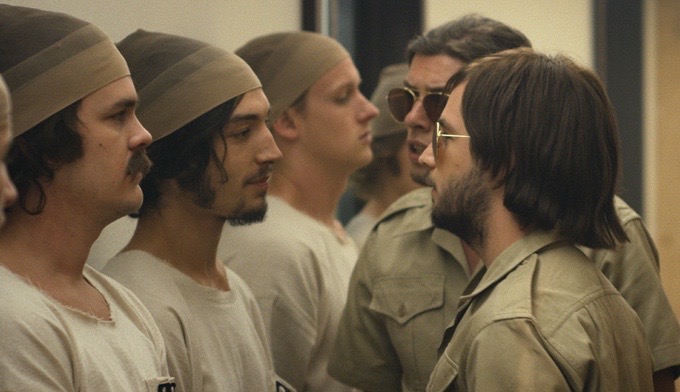

Ezra Miller, center left, faces off against the bearded Michael Angarano, center

right, in Kyle Patrick Alvarez's drama "The Stanford Prison Experiment".

IFC Films

by

Omar P.L. Moore/PopcornReel.com

FOLLOW

FOLLOW

Friday,

July 24,

2015

No one wants to be a guard at the start of “The Stanford Prison

Experiment” but very soon some of these able-bodied citizens will fall right in

line. “The Stanford Prison Experiment” left me less disturbed than

nonplussed, undercutting its potency. The August 1971 Stanford University

experiment on authority, abuse and submission with 23 white male students and

one Asian male student in Palo Alto, California, was to last two weeks.

But the “prisoners” extreme distress and trauma — and researcher Christine

Maslach’s admonitions to now spouse then-boyfriend and Stanford study creator

Dr. Philip Zimbardo to stop — ended the

experiments after six days. Those admonitions aren’t clearly revealed and are

only barely implied, which does the viewer, and more importantly Professor

Maslach, a disservice.

Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s drama is a mildly disturbing account of how authority is

readily acceded to among many personalities, including those otherwise meek and

mild. Some of the test cases — all of whom are promised $15 a day, quickly

buckle under timeless conditions of no sunlight or windows. Others are

defiant. This tension and combustion defines the discomfiting atmosphere and

razor's edge upon which “Stanford” is dispassionately and devastatingly perched.

Yet Mr. Alvarez’s film sabotages that effectiveness with a needless epilogue of

interviews that explain and interpret what we’ve just seen. The epilogue made

me feel the director sometimes didn’t trust enough in the intelligence of his

audience. I wasn't made uncomfortable enough. And the neat bow

that tries to wrap things up pulled my admiration of “Stanford” down several

pegs.

Granted, the film’s quiet power is undeniable, and Billy Crudup, who plays Mr.

Zimbardo, a man who was a tad unhinged at the time, is utterly magnetic and

arresting to watch. The film’s contours, with its tight shots, close-ups and TV

screen views, propel us into the labyrinthine constraints of the mock prison,

held in a Stanford hallway during a summer on a barren campus.

Memorably, “Stanford’s” strength is in the experiment that infects and affects

not the prisoners (Stanley Milgram’s 1960s Yale experiments revealed similar

findings) but administrators like Dr. Zimbardo who ran it. The experiment works

on him, too, unearthing the unregulated appetites that too much authority — or

an absence of it — does. The “on” switch stays on. Dr. Zimbardo indulges his

basest desires. The film’s lone Black character (Nelsan Ellis), a former San

Quentin prisoner, is deeply troubled by how easily he himself slips into

authoritarian mode during a parole hearing. It’s too much for him to bear.

After seeing “The Stanford Prison Experiment”, a bland title but one that’s

necessarily minimalist, I thought of

“Compliance”,

a stronger and intensely unsettling film

predicated on very real and similarly-themed bows to authority. There’s also

“Experiment” (about Mr. Milgram), among other films.

As I watched “Stanford” I thought of Sandra Bland,

Kalief Browder, the Central Park Five,

Abu Ghraib, and Guantanamo Bay. All of these

abusive horrors and a million others — when cast in the primal deep of human

beings and within a fiercely authoritarian culture in the U.S. — are

inextricably linked. With their badges and guns police inherently compel

obedience. Without regulation and with institutional

backing in a system that lacks accountability and doesn't confer any upon them,

brutal and crooked police continue to run amok. So-called good police

remain silent, blue wall or no blue wall. Similarly, regular civilians do

too. (I explain this in great detail

here.)

In some ways, and not only due to these troubling times but because this film

should have been far more powerful and incisive, “The Stanford Prison

Experiment” felt distant: old and stale, compromised by safety (thanks to the

profligate epilogue), and, unlike the aforementioned “Compliance”, not

confrontational or provoking enough.

For me Mr. Alvarez’s film is softened by history, indeed all of human history.

What’s so remarkable and noteworthy, I thought, about a film predicated upon an

experiment that shows us the uglier depths of human souls? After all, human

history and daily practice shows that a sizable number of us haven’t learned to

regulate our worst selves. We override ourselves to seek control over our

environment and even in the most innocuous interactions, seek control over

others. We inevitably try to survive, and we exhale that amazingly we made it

through another day without getting killing or being killed. (Some of us do,

anyway.)

After all, we each have the capacity to do unspeakable things. Only our

consciences can put up a huge red light. If all the wars around the globe and

killings over centuries haven’t convinced us of that, then why should “The

Stanford Prison Experiment”?

One other interesting question: what if Dr. Zimbardo had assembled 24 women for

his experiment? Or 24 Black men? Would the results be the same?

Most likely. Would the experiment have ended earlier or later?

The experiment as depicted in Mr. Alvarez's contained

film extends to the reinforcement of gender roles in a sexist society. One

telling scene features the mother of one participant who is clearly concerned

for her son's welfare. Dr. Zimbardo brushes off her concerns by challenging the

masculinity of her husband with a male solidarity exercise that makes the

husband patronize his own spouse and

relegate his son's agency and safety in front of Dr. Zimbardo at the same time.

The wife, clearly distressed, quietly departs, but not before correcting herself

and calling Mr. Zimbardo "Doctor Zimbardo". The white male power

environment, not the experiment, is working her. It's a subtle but

incredibly telling moment.

It's not just authority, but male authority -- white male authority -- that

fuels the power dynamic and re-oppresses the women characters in the film, who

have come from or are aware of an environment of women that have (presumably)

been fighting for equal rights and autonomy (and burning bras) in 1971. Ms.

Maslach, who married Dr. Zimbardo in 1972, is treated in the film

condescendingly by her husband-to-be. Dr. Zimbardo is the literal and

symbolic male power who continuously asserts himself. His twitchy, ogre-like

dominance however, is less far-reaching than he thinks it is. All along

he's being played, it appears, by his own experiment. And I found that

more interesting than almost everything else that transpires.

Note: Mr. Alvarez’s film is based on Dr. Zimbardo’s book “The Lucifer

Effect”.

Also with: Ezra Miller, Tye Sheridan, Jack Kilmer, Ki Hong Lee, Logan Miller,

James Frecheville.

“The Stanford Prison Experiment” is rated R

by the Motion Picture Association Of America for language throughout, and some

violence. The film's running time is two hours and three minutes.

COPYRIGHT 2015. POPCORNREEL.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.  FOLLOW

FOLLOW

MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

| PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

FOLLOW

TWEET

FOLLOW

TWEET FOLLOW

FOLLOW