MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

|

PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

Sunday, January 11, 2015

POPCORN POLITICS

With "Selma", Will The Academy Catch Up To A Contemporary

And Activist America?

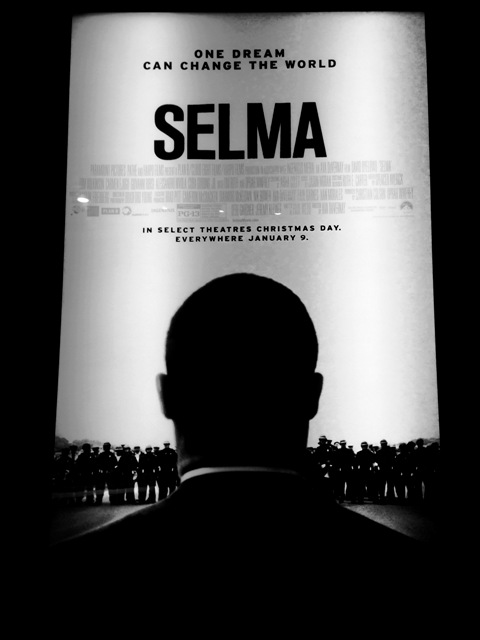

A scene from

Ava DuVernay's film "Selma."

Paramount Pictures

by

Omar P.L. Moore/PopcornReel.com

FOLLOW

FOLLOW

Sunday,

January 11,

2015

In 2014 the beloved and near-universally critically acclaimed

"12 Years A Slave"

became the only film to

interrupt an 85-year-string of white-directed Best Picture

winners. The triumph of "12 Years" can be bluntly explained: it

genuflected to white male saviors. This ingredient is something the

Academy's predominant white male 60-and-over demographic likely felt comfortable

voting for. (Not to mention, of course, that

Steve McQueen's excellent film was supremely

well-made celluloid discomfort.)

As Academy nominations near (Thursday) once again another acclaimed film by a

Black director, "Selma,"

is a serious awards contender. Like "12 Years," moviegoer and critic alike

agree that "Selma" is well-made, excellent and undeniably powerful. As

directed by Ava DuVernay,

"Selma" moves all who see it in deeply profound ways. There rarely exists

a screening during which sobbing and sniffing isn't heard.

Yet several things about "Selma" are notably different: it is directed by a

Black woman, a demographic never granted entry into Academy Award

nominated-director circles. Temporally "Selma" occurs in 1965, more than

100 years after "12 Years." And, perhaps most importantly, unlike "12

Years," "Selma" is without a white savior. The perspective "Selma"

fashions is of a movement shaped by Black leadership that transforms white

consciousness. Black leadership and Black figures in the movement for

voting rights in the "Selma" South is the film's only savior. In

"Selma" any white participants in the movement are soldiers under Black command,

not their saviors.

These important distinctions mean "Selma" doesn't provide the typical safe

distance for its white viewers (or more to the point its white Academy voters.)

No white male character steps into the breach in "Selma" to exact a patriarchal

maneuver rescuing Blacks from the blight of oppression. The Blacks in

"Selma", led by Dr. King (David Oyelowo) chart their own course, galvanizing

whites, including President Lyndon Johnson, to appeal to their better angels.

The violence of Bloody Sunday, which Ms. DuVernay's film splendidly chronicles

is, as in real life, a turning point for the film's whites to self-activate from

their shame, confront it and use their white privilege to solidify an already

powerful movement into an even greater unassailable crescendo against racist and

fascist enforcements against Black and white Americans.

In this respect "Selma" is an active advocacy film that compels our consciences

in the American here and now. On its surface "Selma" is

non-confrontational but its underbelly is resoundingly otherwise. It is

urgent, whereas "12 Years," albeit a vivid chronicle of Solomon Northup, was

not. "Selma" is a direct appeal to advocacy -- specifically the advocacy

of whites on screen and off. "Selma" operates as art in a deeper,

more powerful way than "12 Years A Slave" in that it compels us now and

is about now.

Audiences at large who watch "Selma" cannot escape. White audiences cannot

hide. (I have seen "Selma" four times and I've noticed men, particularly

white men, sobbing during the film.)

Though released by Paramount Pictures "Selma" is a far more independent film

than a Hollywood one. The safe distance whites had from the cruelties of

"12 Years A Slave" -- even with its ferociously violent atrocities -- is far

less safe in "Selma." Ms. DuVernay's film is even less conventional than

Mr. McQueen's because it defies a notion of white saviors. The violence in

"Selma" is less grotesque but arguably more unsettling. There's a

continuum to the violence in "Selma" that persists in 2015. Last week an

NAACP office was bombed with no damage but

the long history of such damage to NAACP offices dates

back decades. In other words, there's no distancing from

continuums.

"Selma," unlike "12 Years," empowers Blacks, giving them self-actualization,

independence. "Selma" depicts Blacks as authentic, strategized figures

full of dimension and definition. They are not cliche types inserted for

the benefit of white moviegoer comfort and guilt relief. The Blacks of

"Selma" have a higher divinity, consciousness and moral authority than the white

men (LBJ, George Wallace, Sheriff Jim Clark) in various levels of American

political power. Blacks in "Selma" aren't desperate or despairing or

helpless. They are urgent. They don't wait for saviors. They

act. There's a big difference. A big difference also to the

historical representation of Blacks on film in Hollywood.

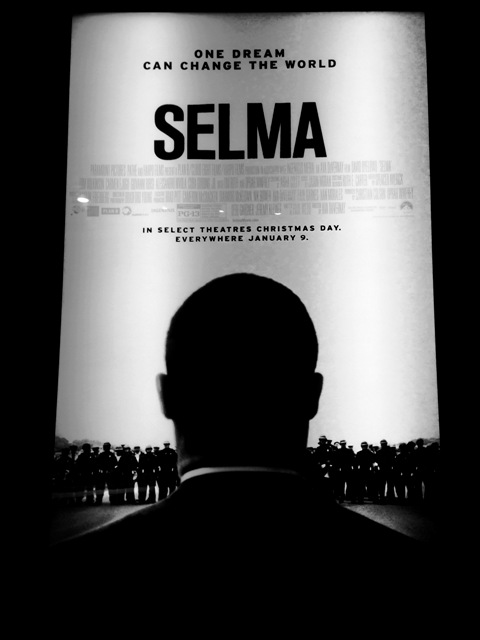

Timeless: The poster, in black and white, for Ava DuVernay's film "Selma."

[Note: What is remarkable about "12 Years A Slave" and "Selma" are that many of

the leads in both are British. Mr. McQueen is British, and actors Chiwetel

Ejiofor, Benedict Cumberbatch and Michael Fassbender are from the UK. Mr.

Oyelowo, Carmen Ejogo, Tom Wilkinson and Tim Roth are all British. Both

films were produced by Brad Pitt's company Plan B.]

We've seen films with the force and inspiration of "Selma" marginalized by the

Academy before. Spike Lee's "Malcolm X" was a prime example. Great

acclaim by critics and audiences. Great performance in the title role by

Denzel Washington. Yet the Academy handed Mr. Lee's film just two Oscar

nominations including costume design, in 1993.

Oscars don't define or contextualize cinematic brilliance. Many a film

with poor artistic merit and message has been adorned with Oscar. Many

Oscar-winning films have been long forgotten while superb non-Oscar-winning

films endure and are stil lauded. But it is important that America's most

prestigious body -- the Academy -- which consists of those who create and

participate in Hollywood's and the world's most prominent projections on screen,

speaks up about American history through its choices and appears far less

regressive than its very demographic suggests. An industry which lauds

itself as "liberal" should do this at the very least.

When the brutalization of Bloody Sunday occurs in "Selma" there's a moral force

that guides its most powerful moments, putting the violence depicted in a

context that is visceral and condemning. (The violence in "12 Years" is

more unblinking and neutral by comparison.) "Walk With Me," sung by Martha

Bass, plays while savage beatings by state troopers are inflicted upon Blacks.

Ms. Bass's gospel voice echoes through the violence as a guide and appeal to

conscience. The song sears, speaking not just to a higher power but to the

higher reaches of consciousness within whites in the moviegoer audience watching

"Selma."

The distance for white viewers and Academy voters shrinks even more when you

consider the very recent American history of Selma and Bloody Sunday of March 7,

1965. There don't need to be, and aren't, subtitles in "Selma" that say,

"1965." That's no accident. "Selma" is a direct missive implying

that the 1965 American state-sanctioned assault on the Black body and Black body

politic is the present-day American atmosphere through which it reverberates.

The "Selma" moviegoing audience itself associates with the events of now,

bringing them into the movie theater even before "Selma" plays on the screen.

America is living them now. Especially Black moviegoers in America.

"Selma" is about voices of conscience, not physical suffering or subjugation.

Ms. DuVernay's film is told unblinkingly through compassionate, resolute and

wholesomely inclusive eyes. The women of "Selma" are given a sizable

tender of the stage. Their contributions to the 1950s and 60s Civil Rights

movement are restored. The whites who join the movement fight alongside,

not ahead or in place of, the Blacks whose movement it unmistakably is.

The viewing distance for the white moviegoer and Academy member is further

obliterated because of the most recent violence against Blacks right now in

America by state-sanctioned authorities. There isn't a soul alive today

above age 20 who hasn't at least heard of the names Eric Garner, John Crawford,

Michael Brown or Tamir Rice. Each was Black, male, unarmed and killed by

police in 2014. (There have been Black female victims, too.) Three

were killed while video recorded their last breaths. Protests against

their deaths and the injustice engulfing them and many others are ongoing, by

whites as well as Blacks.

With "Selma" there's a palpable conflation of art and real life, and in a

positive, enthralling but not manipulative sense. As you watch "Selma" you

are constantly reminded of it. Ms. DuVernay shot her film before each of

these young men above were killed, yet her dialogue, as delivered by Mr.

Oyelowo's Dr. King, feels ripped from today's headlines more than from 1965.

That is eerie. It is eerier when you consider that

in 2013 the U.S. Supreme Court eviscerated a major part of

the very Voting Rights Act Dr. King pushed LBJ to sign on August 6,

1965. This last point is the unspoken coda to "Selma" that is arguably

more damning than some of what we see in the film.

In "Selma" several shots of Dr. King show him looking directly at us. He's

talking through the screen to his 21st century audience from the grave.

For some this isn't a comfortable experience. Mr. Oyelowo is so compelling

in those moments. He speaks about white politicians and white privilege in

the impassioned tones that resonate, and surely sear through the hearts of some

white viewers. I think he pens some of the viewers to their seats.

Fixates and compels them.

In that King moment and throughout "Selma" history is placed squarely in the

laps of the white audience (and Academy voters.) "Selma" is alive and its

truths can't be refuted. When you see it, you know it, associate it and

feel it. "Selma" speaks more to awakening the white consciousness

of the 21st century than to Black consciousness. Many Blacks already

understand it. Yet even they haven't seen a Hollywood-made film of such

grandeur and poetry as "Selma." It's a film that represents and

diversifies Blacks, Black women and all others well. It nourishes Blacks,

their souls, and all souls, affirming the humanity of the Black people it

depicts.

Ava DuVernay directing David Oyelowo on the set of "Selma."

Paramount Pictures

The Academy has generally not been partners with films that don't allow their

members to breathe. There may be some exceptions but generally for the

Academy history itself is a commodity on film that must ultimately be feel-good.

"Gone With The Wind" made slavery gleeful. Blacks in it were seen as

content, compliant and willing figures. That specific film won Oscars,

including Best Picture, 75 years ago.

The degree of nostalgia in film is often a better harbinger of Oscar success

than a film or present historical impart is. White Academy voters over the

age of 60 lived through the events of Selma, Alabama. No matter whether in

the South or North they likely have memories. "Selma", as dazzling and

brilliant a film as it is, doesn't provide white audiences with the opportunity

to feel good about themselves, though in the film's second half it gives them

strong reason to be proud.

That "Selma" is so unmistakably alive isn't solely due to Ms. DuVernay's keen,

sensitive approach to a collective, affirmative representation of Blacks on

film. It's also because the events of now help make "Selma" so alive.

What Ms. DuVernay's film does is complete the full, proper image of Dr. King and

a movement with a broader, restorative brush, erasing the hallowed and empty

corporate mainstream media realms and capitalist strictures that Dr. King and

his memory has traditionally lived and been mired in.

At the same time the Academy is being challenged by a new generation of

filmmakers, Black and white alike. The Academy's traditions and notions of

award-worthiness are being challenged in this the 21st century. Never in

the 86 years of the Academy Awards has a Black woman-directed film been

nominated for a Best Picture Oscar. On Thursday Ava DuVernay is poised to

become the only Black woman to be nominated for a Best Director Oscar.

The atrocious statistic above reveals that the Academy is a far more

regressive body in its lack of Black winners than are U.S. institutions of

political power to Blacks. A Black president of the United States has been

elected before a Black woman has been nominated for a Best Director Oscar.

There have been more Black women U.S. senators (1) in American history than

Black Best Director Oscar winners (0). There have been more Black women

Academy presidents (1, currently serving) than Black women Best Director

nominees (0). That's the ambit of American history and climate in which

Ava DuVernay's "Selma" operates.

When Mr. Oyelowo's King says "all-white juries" in 1965, you think of today's

virtually all-white grand juries in Staten Island (Eric Garner) and Ferguson

(Michael Brown) and the trial jury in Simi Valley (Rodney King). By

extension, outside that political realm you may think in the Hollywood

entertainment realm. You may think of

Sony Pictures co-chair Amy Pascal's

emails to

Scott Rudin. You may think about the Academy itself and where it

stands on Blacks both in representation and Oscar winners.

The statistics on the

Academy's racial makeup, for example,

speak loudly

for themselves.

Ironically, "Selma" is the kind of large, consciousness-raising film that fits

the paradigm of a Best Picture Oscar winner. It has size, scope, charm+

and measured tones of deep seriousness. It is also compelling.

"Selma" has moralistic force and grandeur. It has nobility and a clear,

strong message.

More than any of its prospective fellow Oscar competitors, "Selma" is

electrifying and breathes deeply into the heart of right now. The

only question will be how "Selma" will be viewed by the Academy. Will

"Selma" be viewed within the context of 1965 or the context of 2015? Does

that question even matter, given continuums of injustice against many who are

represented by only 2% of the Academy? March 7, 2015 is the 50th

anniversary of Bloody Sunday in Selma. Will "Selma" have been celebrated

by the Academy by then? "Selma" is a film about current and recent

American history that the Academy will either remove itself from or turn its

back on, or embrace.

Thursday morning will be a referendum on whether a near-all-white body of

artists, producers and celebrities will confront America's very recent history

-- and its present. This challenge is the very challenge that "Selma" as a

film presents to its white viewers. Our umpteenth chance to have a sincere

and honest dialogue about race, racism and injustice is presented by "Selma".

Does the Academy want to further buttress, facilitate or endorse the idea of

that conversation with a fulsome bestowal of Oscar nominations to Ms. DuVernay's

film? Or will it evade that conversation on race, like far too much of

white America has? That will be the question this Thursday.

Will "Selma" at the Oscars be reduced to a song? Will American history and

a discussion of it be symbolically squelched and marginalized in the awards

nominations or on Oscar night by a supposedly "liberal" film awards body?

That is the question.

The challenge for the Academy is to pry itself from the yolk of safe nostalgia

it has traditionally rewarded and celebrated on the big screen and come forward to 2015.

To not give "Selma" its proper due -- namely a hatful of Oscar nominations on

Thursday -- would be to send the message that the Academy is still safely stuck

within the confines of yesteryear. The Academy's membership ratios, with

its distinctly small but glacially-changing percentages of race and sex

representation, further indicate that it is stuck there. In the past. Will the Academy,

like the BAFTAs last week, which awarded "Selma" with no nominations,

firmly keep its blinders on in a real world that presently turns and evolves around it?

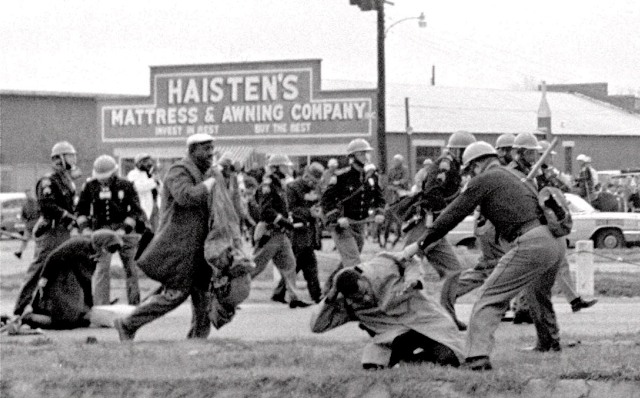

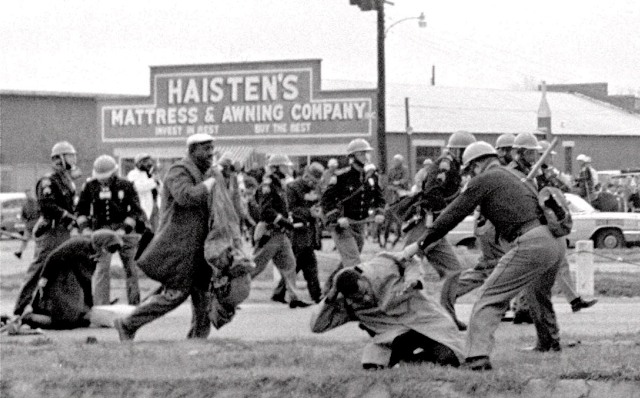

John Lewis, right hand side, being beaten by an Alabama

state trooper in Selma on March 7, 1965. Associated

Press

White protesters, as they did in Selma, Alabama, and in "Selma", are now joining

movements engineered by Blacks due to the unjust killings of Blacks in 2014.

The hashtag

"Black Lives Matter", an anthem of today's new movement,

was started by Black women.

The Selma

marches were started by a Black woman. "Selma" and reality

converge to an inseparable point that inevitably confront all. Will the

Academy through its choices prove once again that the evils of 100 years ago are

a safer place in which to reward artistic excellence? Or will it break the

mold and go bold?

American society today has progressed to a small degree from 1965 but American

mainstream media is more regressive. With

some exceptions many mainstream media outlets were

initially slow to report on the NAACP bombing in Colorado

Springs last week. U.S. Congressman John Lewis, who was at the

heart of the 1965 Selma marches and is played by

Stephan James

in "Selma",

expressed grave concern.

By contrast, corporate media

entities have given substantially more air time to an orchestrated LBJ "controversy"

that is non-existent in

"Selma." The loud noises made by a very small few around "Selma" and LBJ

are cries for reinforced patriarchy and saviors that maligned past films.

These cries aren't about historical accuracy. They are about Oscar campaigns,

competition

and money.

Many a film has won Oscars while they have disregarded or rewritten history.

Historical accuracy wasn't the Academy's concern in such instances.

"Mississippi Burning" was one of the biggest recent misnomers. Yet it

still won an Oscar (for best cinematography.) Steven Spielberg's

"Lincoln" also had

questions about its omissions and inaccuracies. It won an Oscar.

David Oyelowo and Colman Domingo were two of the only three Blacks in "Lincoln."

(The other appeared at the very end.) Both actors appear for about 30

seconds. Both are in "Selma" for a lot more time than that.

Frederick Douglass's absence from "Lincoln" was glaring.

"Selma" accurately depicts art and history. "Selma"

comes with a fine

print disclaimer none will have read, during its end credits.

"Selma" lauds LBJ, a point that other films' Oscar campaign-directed detractors

conveniently ignore. No American TV media pundit or commentator asks any

detractor if "Selma" was a good film. None ever say it was a bad one.

Very few cite that "Selma" is not a documentary. The LBJ controversy is

made to be bigger than it is. Will the mild controversy provide the

Academy -- some of whose members have publically responded enthusiastically to "Selma" --

the excuse to dismiss it?

History isn't of true concern to the Academy. With "Mississippi Burning,"

a film populated with white stars, with Blacks relegated to the background, the

controversy about the FBI, a representation far more egregious than anything in

"Selma", while raised at the time, didn't totally derail Alan Parker's film.

Now that Oscar campaigning has become nastier and more scurrilous, and social

media has come into play, the nature of competition has become a fiercer

battleground.

Some media commentators attacked "Selma" without even having seen

it, a classic trait of orchestration and folly. You can't take such

pundits seriously. Will the Academy?

The Academy has, through its Oscar choices, always been more comfortable

awarding films portraying the dehumanization of Blacks over those films that

show fully dimensional Black people or Blacks who independently affirm and

uplift themselves. You can look throughout Academy history

for proof of that certification. "Selma" shows us real Black people, not the reel

Black people America has been bombarded with for a century.

On Thursday there will be a true test of the Academy's introspection. Will

they send a strong message with their nominations? Or will they prove that their safety in

electing to slink back into the shadows of safe film nostalgia and history have a

stronger, more appealing appetite?

Time will tell, and very soon.

COPYRIGHT 2015. POPCORNREEL.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.  FOLLOW

FOLLOW

MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

| PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

FOLLOW

TWEET

FOLLOW

TWEET

FOLLOW

FOLLOW