MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

|

PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

MOVIE REVIEW

Detachment

Connecting To The Disconnection In Today's World

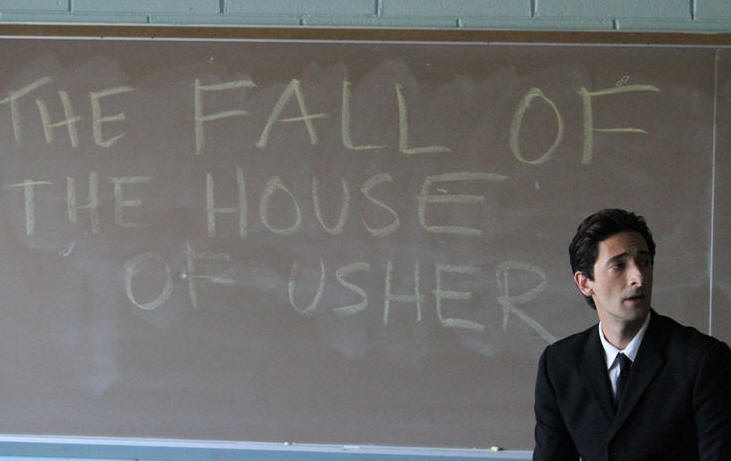

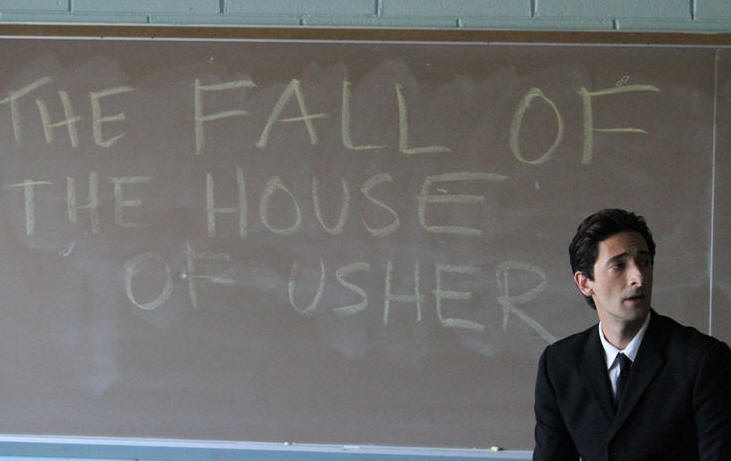

Adrien Brody as Henry Barthes in Tony Kaye's docudrama "Detachment".

Tony Kaye

by

Omar P.L. Moore/PopcornReel.com

FOLLOW

FOLLOW

Tuesday, March 27,

2012

Two quotes bookend Tony Kaye's docudrama "Detachment", now playing in

select cities in the U.S. One is from Albert Camus, the other is from

Edgar Allan Poe. Both inform what has been happening throughout Mr. Kaye's

film, billed as "a Tony Kaye talkie", full of volatility, fragility and anger on

many sides. Henry Barthes (Adrien Brody) is a substitute teacher in an

unnamed "inner-city" New York City high school. Henry cares, or used to

care, about people, about himself, yet he is compassionate but full of anguish

and anger.

Henry, who lives alone, takes in an abused young prostitute, Erica (Sami Gayle),

yet this is perhaps done more to counteract and salve his own sense of inadequacy, frustration and

anger about life than out of any gesture of altruism. Henry teaches in a fruitless effort to change the hearts of

nonchalant kids in a school where teachers are as likely to meltdown as

students. There's a lame-duck principal (Marcia Gay Harden) who has failed

to boost the school's abysmal student test performance. She's depressed.

The despair is universal and "Detachment" often makes the points Henry discusses

redundant. "We are all suffering from pain, and feeling the weight of the

world on our shoulders," is the film's basic refrain, which gets repeated in

golden sunshiny confessionals of clarity that Henry gives, in close-up,

documentary style.

Some of the film's points are trenchant and ham-fisted yet I believe Mr. Kaye is

thoroughly sincere. He wants us to think about what we as young and old

people in today's world are running away from. Is it our past? Our

family? Our failure as a species? Ourselves? Our pain? All of these?

Or something else? Something more? Late on a character intones

about "solutions to temporary problems" and implications resonate. The

denouement we see in "Detachment" isn't unexpected; this angry

hell boat of a film has previewed it in many

flashbacks and spliced edits. Family and its breaking apart is at heart of

"Detachment". Characters wax on about the lack of parents at the

parent-teacher meetings at the school. The parents are as angry as their

children are, and the fragmented film attempts to dissect the anger, especially

from the students, one of whom mutilates a cat (it is unseen but strongly

implied.)

So where does Henry's anger come from? The answer is most likely

in his own family background, which has seen its share of tragedy. We are

offered glimpses of Henry's back story, upbringing, family destabilization and

dysfunction by Mr. Kaye, whose "Detachment" is shot in Super 8mm, lending

raw, grainy and gritty

texture to its carnival of sorrow. Though written by Carl Lund, the drama

operates as the director's manifesto. Mr. Kaye, who has had a lot on his

mind and a lot of anger (and rightfully so) at the way the original edition of

his last major film, "American History X" (1998), was truncated for theatrical release

by the now-defunct New Line Cinema, unleashes it all in a film that feels much

closer to his vision and probing spirit. ("Detachment" is an independent

film being released in roughly a dozen or so venues for its entire U.S.

theatrical run, with New York City and Los Angeles as the only major

metropolitan big cities included.)

As a structured enterprise "Detachment" is clever, presenting its own

diametrically opposed devices (also exhibited during one of Henry's school

lessons), which plays like the absurdist theory of Mr. Camus and resembles parts

of the author's The Stranger. More significantly, the film's

strong connection to disconnection is an anthem; themes of family unrest,

instability and fracture penetrate, recurring throughout the film.

"Detachment" represents tragicomedy at its height and its most ridiculous.

Pure mad theater, lurid, darkly comic and partly outrageous, "Detachment"

creates dissonance and resonance at the same time. It denies itself the

sole pleasure of being cynical while offering hope and promptly spitting in its

face, mocking it openly, with fish-eye close-ups that imitate campy horror.

The film's other focus, or Henry's other cause célèbre besides Erica, is lonely

student and photographer Meredith (Betty Kaye), who observes Henry and his

sadness. Keeping with the film's sense of irony and complexity Meredith's

observation is actually a projection of her own sadness and despair.

Emotionally abused at home, no one listens to her, except Henry, yet Henry

himself rejects, even despises, his "role" as a savior. He'd be the first

to say, in Charles Barkley parlance, that "I am not a role model."

Premiered at last year's Tribeca Film Festival, "Detachment" plays as a satire on goody-two-shoes teachers looking to make a

difference; it is refreshingly honest and shrill, presenting self-centered

teachers who question their own efforts. Everyone in "Detachment" is fully

human, living breathing contradictions, and ill at ease with their own

existence, which is the film's battering ram.

The weakest and most unnecessary part of "Detachment" are black and white

sequences that open the film, with what are apparently real-life school teachers

some of whom didn't expect to fall into that line of work. These extreme

close-ups are part of Mr. Kaye's theme of disconnection and faltering idealism

that reinforce the film's title, but the sense of intimacy they are meant to

convey pales in comparison to the intimacy of the fictional stories on display,

even if they are occasionally interrupted by blackboard animation, some of which

grows tiresome and repetitive, hitting the same points over and over again.

That said, Adrien Brody does possibly the best work of his film career as Henry,

utilizing comic and tragic masks to fine effect as a deeply depressed and

disillusioned yet hopeful teacher. Henry is so clearly resigned to a bleak

outcome that when sad things happen he flaunts a noblesse oblige attitude.

"It's okay. It's okay. It's okay to let go." Mr. Brody makes

these utterances at once oddly comic and bleak even if his Henry means every

word of them. (Note: William Petersen is in this film, and I still don't

know if I saw him on screen. Like Albert Brooks in "Drive", I couldn't

recognize who he was. And unlike that film, I still don't know that I even

saw or recognized him.)

For all its own wildness and frenzied application "Detachment" is a must-see

solely for Mr. Brody. While there are good ensemble performances (Ms.

Gayle and particularly Lucy Liu, James Caan and Tim Blake Nelson as teachers

who've seen a little bit more than too much both at home and at school,) the

lead actor puts on a great balancing act. Henry is the absurd creation

resulting from the school's chaos but that crumbling house reflects the unstable

foundations of his family background, which he had long before he visited.

Is the school of chaos some kind of reconciling for Henry? Is the school a

kindred spirit or amplified character that affirms Henry's own sense of

loneliness, an isolation met elsewhere by those he teaches and the colleagues he butts heads

with? Mr. Brody deftly carries the burden of Henry, supplying him with

equanimity and a jarring disharmony, even in the film's nihilistic and

catastrophic bursts. (Note: Eagle-eyed viewers will notice the MPAA logo

in the end credits, with the film falsely and playfully registered as No.

999999, creating its own detachment. The number of films registered is

about 49000 or so.)

Mr. Brody, who won an Oscar in 2003 for "The Pianist", bores holes through the

screen here with sad eyes and a big heart swelling with empathy and emptiness.

In "Detachment" he paints a full, palpable portrait of a troubled man wrestling

with existential angst and his relationship to the crazy world that spins out of

control around him. He spins with it but he tries to get off before it's

too late.

"These kids need something, but they don't need me," Henry says in the film's

final half hour. Henry is half-right -- the kids need Henry's help, not

his anger or pity.

With: Christina Hendricks, Blythe Danner, Bryan Cranston, Louis Zorich, Isiah

Whitlock Jr.

"Detachment" is not rated by the Motion Picture Association Of America

but it contains some disturbing images including a close-up of a diseased

vagina, sexual content, nudity, strong

language, intense moments and thematic issues. The film's running time is one hour and

38 minutes.

COPYRIGHT 2012. POPCORNREEL.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.  FOLLOW

FOLLOW

MOVIE REVIEWS |

INTERVIEWS |

YOUTUBE |

NEWS

|

EDITORIALS | EVENTS |

AUDIO |

ESSAYS |

ARCHIVES |

CONTACT

| PHOTOS |

COMING SOON|

EXAMINER.COM FILM ARTICLES

||HOME

FOLLOW

TWEET

FOLLOW

TWEET FOLLOW

FOLLOW